Chan Xiang Lam | 0358400

Typography | Bachelor of Design (Honours) in Creative Media

Task 1 | Exercises 1 (Type Expression ) & Exercises 2 ( Text Formatting)

LECTURES

Lecture 1 | Briefing / Introduction

1.1 What is Typography?

- Typography can be defined as the art of creating letterforms, involving

elements like letter construction, grid usage and classic proportions. It is

use to designs the shape of letters that you see in printed or digital media.

Therefore, typography involves the creation of typefaces or type families.

1.2 Type History

1. Early Evolution of Roman Letters 1

Early evolution of roman letters specifically focusing on Roman capital

letters and their transition into more practical writing styles. It introduces

three distinct handwriting styles : square capitals, rustic capitals and roman

cursive.

-

Square Capitals: Theses were formal letters influenced by

inscriptional forms. They were meticulously drawn but written more quickly

than stone inscriptions.

Figure 1.2.1 Example of Square Capitals

-

Rustic Capitals: These were narrower and simpler letterforms,

developed to save space and time in producing less important documents.

Figure 1.2.2 Example of Rustic Capitals

-

Roman Cursive: This was a more fluid and speedy handwriting style

suitable for business transactions, bookkeeping and correspondence. It

became the standard for everyday use until around AD 500.

Figure 1.2.3 Example of Roman Cursive

2. First Alphabet

The text traces the early development of writing from simple tokens

to symbols, and then to phonetic alphabets. It highlights the

contributions of civilizations like the Egyptians and Phoenicians in this

evolution. The Phoenicians introduced the first phonetic alphabet focused on

practicality Phoenicians introduced the first phonetic alphabet

focused on practicality and record-keeping. The Greeks further refined the

alphabet by adding vowels and curves. The Latin alphabet, based on Greek

letterforms, was adopted and adapted by the Romans. Roman capital

letters, used in monumental inscriptions, have influenced the

design of capital letters for over two millennia.

Figure 1.2.4 Example of First Alphabet

Lecture 2 | Development / Timeline

2.1 Early Letterform development: Phoenician to

Roman

In the early phases of writing, people used tools like sharpened sticks on wet

clay or chisels on stone to create letters. The uppercase letterforms, which

remained prominent for about 2000 years, originated from these basic tools and

materials. They were formed by combining straight lines and circular segments

due to the limitations of the available writing materials and tools.

Figure 2.1.1 Example of Phoenician Letterform

The Greeks revolutionized writing by introducing 'boustrophedon', a method

where text was read alternately from right to left and left to right. Unlike

the Phoenicians and other Semitic cultures that wrote exclusively right to

left, this style mimicked the ox's ploughing pattern.

This change in reading direction also led to significant adjustments in

letterform orientation, impacting the evolution of writing systems in a

profound way.

Figure 2.1.2 Example of Greek Fragment

Etruscan and later Roman craftsmen, especially those working with

marble, had a meticulous approach to lettering. They would initially paint the

letter shapes before carving them, ensuring specific details like the

transition in stroke thickness from vertical to horizontal and widening

strokes at the letter's start and end. These painted attributes were

faithfully replicated in the final carved letterforms.

Figure 2.1.3 Example of letterform from Phoenician to Roman

2.2 Hand script from 3rd - 10rd century

C.E.

The 3rd to 10th centuries C.E., various styles of

handwriting emerged:

-

Square Capitals: Like Roman inscriptions, these used varied

stroke widths with a reed pen at a 60° angle.

Figure 2.2.1 Example of Square Capital

-

Rustic Capitals: Condensed version of square capitals for

faster writing and more words per parchment.

Figure 2.2.3 Example of Rustic Capitals

-

Cursive Hand: Simplified for speedy everyday transactions.

Figure 2.2.4 Example of Cursive Hand

-

Uncials: Incorporated elements from Roman cursive, enhancing

readability at small sizes.

Figure 2.2.5 Example of Uncials

-

Half-Uncials: Formalized cursive hand with ascenders and

descenders, introducing lowercase letterforms after 2000 years.

Figure 2.2.6 Example of Half-Uncials

-

Charlemagne: In 789, mandated standardization of ecclesiastical

texts, led by Alcuin of York, shaping calligraphy for a century.

Figure 2.2.7 Example of Carolingian minuscule

2.3 Blackletter to Gutenberg's type

Regional script variations followed Charlemagne's empire dissolution.

Blackletter (textura) rose in the north for its condensed style, while the

south favored the rounder 'rotunda'. Italy adopted the humanistic script.

Gutenberg's diverse skills in engineering, metalsmithing, and chemistry

enabled him to replicate the scribe's hand, particularly Blackletter, using

specialized type molds and brass matrices for each letter.

Figure 2.3.1 Example of Blackletter

2.4 Text type classification

Figure 2.4.1 Example of text type classification from 1450-1990

Lecture 3 | Text / Tracking: Kerning and Letterspacing

Definitions for kerning, letterspacing and tracking in typography :

- Kerning : Adjusting space between individual letters.

Figure 3.1.1 Usage of kerning

-

Tracking : Encompasses both adding and removing space in a

word or sentence for overall spacing adjustment, making it a broader

term that includes kerning and letterspacing.

Figure 3.1.2 Usage of normal tracking, loose tracking and tight

tracking

-

Letterspacing : Adding space between all the letters in a

word or sentence.

Figure 3.1.3 Example of Normal tracking, Loose tracking and

Tight tracking

3.2 Text / Formatting Text

-

Flush left: Resembles handwriting with consistent starting

points and varying line endings. Even spacing between words creates a

uniform appearance.

Figure 3.2.1 Example of Flush left

-

Centered: Creates symmetry, turning text into shapes. Careful

line breaks are needed to prevent jagged edges.

Figure 3.2.2 Example of Centered

-

Flush right: Emphasizes line endings, useful for situations

like captions where orientation matters.

Figure 3.2.3 Example of Flush right

-

Justified: Achieves symmetry by adjusting spacing between

words and letters. However, it can result in "rivers" of white space,

requiring careful line breaks and hyphenation for correction.

Figure 3.2.4 Example of Justified

3.3 Text / Texture

Typefaces goes beyond history. It's vital to choose one that matches the

message. Consider the texture too. Fonts with larger x-height or bolder

strokes appear denser on the page. This sensitivity is key for effective

layouts.

Figure 3.3.1 Anatomy of A Typeface

Figure 3.3.2 Different typefaces with different grey scale

3.4 Text / Leading and Line Length

-

Text size: Text type should allow for easy reading at arm's

length, as if holding a book in your lap.

-

Leading: Adequate leading prevents vertical eye movement, while

avoiding excessive leading prevents distracting striped patterns.

-

Line length: Line length along with type size and leading,

influences appropriate leading. Aim for 55-65 characters per line, as

extremely long or short lines hinder readability.

Figure 3.4.1 Left: Bad Leading Right: Good Leading

3.5 Text / Type Specimen Book

A type specimen book presents typefaces in various sizes for evaluation.

Without printed samples, it's challenging to make an informed choice. Final

decisions for on-screen reading are best made on screen. A type specimen book

(or screen-compatible ebook) serves as a precise reference for type, size,

leading, line length, and more.

Figure 3.5.1 Sample Type Specimen Sheet

Lecture 4 |

Text / Indicating Paragraphs

There are several options for indicating paragraphs

:

-

Pilcrow - The "pilcrow" (¶) symbol, derived from

medieval manuscripts, is now rarely used.

-

Line Space - If the line space is set at 12pt, the paragraph

space will also be 12pt, ensuring consistent alignment across text

columns.

Figure 4.1.2 Line Space

Figure 4.1.2 Line Space vs Leading

-

Standard Indentation - Which is usually equivalent to either the

line spacing or the point size of the text.

Figure 4.1.3 Standard Indentation

-

Extending Paragraphs - While resulting in unusually wide text

columns, may be chosen for compelling compositional or functional

reasons, despite potential challenges.

Figure 4.1.4 Extended Paragraphs

4.2 Text / Widows and Orphans

In traditional typesetting, there are two unpardonable gaffes widows and

orphans.

-

Widows: These are short lines of type left alone at the end

of a column of text.

-

Orphans: These are short lines of type left alone at

the start of a new column.

Figure 4.2.1 Example of Widows and Orphans

In traditional typesetting, widows and orphans are big no-nos,

especially in justified text. While other alignments are more

forgiving to widows, orphans are still a concern. To fix

widows, tweak line endings to avoid short lines. To tackle

orphans, pros make sure no column starts with the last line of

a paragraph.

4.3 Text / Highlighting Text

Different types of emphasis necessitate varying

levels of contrast within a column of text. This principle guides

how we highlight specific content effectively.

Figure 4.3.1 Example of Text Highlight

In this example, the sans serif font Univers has been reduced by 0.5

to align its x-height with the serif typeface, resulting in a font

size of 8 (originally 7.5).

Figure 4.3.2 Example of Reduced The Sans Serif Font (Univers)

Aligned figures (numbers) and all-capital

acronyms embedded in text are also reduced by 0.5 to maintain visual

consistency with the rest of the text.

Figure 4.3.3 Example of Reduce size of text to

ensure visual cohesion of text

When highlighting text with a colored background, it's crucial to

maintain the left reading axis (as shown in the right example) to

ensure optimal readability.

Figure 4.3.4 Example of Highlighted Text Through Coloured Background

Occasionally, certain typographic elements need to extend outside

the left margin of a column of text (rather than indenting) to

preserve a strong reading axis.

Figure 4.3.5 Example of Typographic elements outside the left margins

Quotation marks, like bullets, can disrupt the left reading

axis by creating a noticeable indent. A comparison between the

indented quote at the top and the extended quote at the bottom

illustrates this.

Figure 4.3.6 Example of Using Quotation Marks

4.4 Text / Heading within Text

Text within chapters can be subdivided into different levels of

importance, labeled as A, B, and C in the provided visuals. The

typographer's responsibility is to ensure that these headings

effectively communicate their relative importance and their

relationship to one another to the reader.

"A" heads mark clear breaks in topics, presented larger in

small caps and bold. The fourth example extends the A head to the

left.

Figure 4.4.1 'A' head

"B" heads, subordinate to A, introduce supporting

arguments or examples. They're in small caps, italic, bold serif, and

bold sans serif.

"C" heads, less common, emphasize specific

facets in B head text. They blend smoothly, in small caps, italics,

serif bold, and san serif bold. An em space follows for separation.

Figure 4.4.3 'C' head

4.5 Text / Cross Alignment

Aligning headlines and captions with text type enhances the

page's architectural structure and reinforces its vertical

rhythms. In the provided example, four lines of caption type

with 9 points leading align with three lines of text type with

13.5 points leading.

Figure 4.5.1 Example of Cross Alignment of text

Below, one line of headline type aligns with two lines of

text type, and on the bottom left, four lines of headline type

align with five lines of text type.

Figure 4.5.2 Example of Cross Alignment of text

Lecture 5 |

Basic / Describing letterforms

Typography, like any long-evolving craft, employs a range of

technical terms, primarily to describe distinct elements of

letterforms. Familiarizing oneself with this lexicon is

beneficial, as it facilitates the identification of specific

typefaces by understanding their component parts.

-

Baseline: The imaginary line serving as the

visual base of letterforms.

-

Median: The imaginary line that defines the

height of letterforms.

-

X-height: The height of the lowercase 'x' in any

typeface.

Figure 5.1.1 Example of Baseline, Median and

X-height

-

Stroke: Any line defining the basic letterform.

Figure 5.1.2 Example of Stroke

-

Apex/Vertex: Point created by joining

two diagonal stems.

Figure 5.1.3 Example of Apex/Vertex

-

Arm: Short strokes off the stem of a

letterform, either horizontal or inclined upward.

Figure 5.1.4 Example of Arm

-

Ascender: Portion of the stem projecting

above the median.

Figure 5.1.5 Example of Ascender

-

Barb: Half-serif finish on some curved

strokes.

Figure 5.1.6 Example of Barb

-

Bowl: Rounded form describing a counter,

which can be open or closed.

Figure 5.1.7 Example of Bowl

-

Bracket: Transition between the serif

and the stem.

Figure 5.1.8 Example of Bracket

Figure 5.1.9 Example of Cross Stroke

-

Crotch: Interior space where two strokes

meet.

Figure 5.1.10 Example of Crotch

-

Descender: The segment of a lowercase

letterform's stem that extends beneath the baseline.

Figure 5.1.11 Example of Descender

-

Ear: Stroke extending from the main stem

or body of the letterform.

Figure 5.1.12 Example of Ear

-

Em/en: Originally referred to the width

of an uppercase M; now refers to distances equal to

the size of the typeface.

-

Finial: Rounded non-serif terminal to a

stroke.

Figure 5.1.13 Example of Finial

-

Leg: Short stroke off the stem of a

letterform, either at the bottom or inclined

downward.

Figure 5.1.14 Example of Leg

-

Ligature: Character formed by combining

two or more letterforms.

Figure 5.1.15 Example of Ligature

-

Serif: Right-angled or oblique foot at

the end of a stroke.

Figure 5.1.16 Example of Serif

-

Link: Stroke connecting the bowl and

loop of a lowercase G.

Figure 5.1.17 Example of Link

-

Loop: In some typefaces, the bowl created

in the descender of the lowercase G.

Figure 5.1.18 Example of Loop

Figure 5.1.19 Example of Shoulder

-

Spine: Curved stem of the letter S.

Figure 5.1.20 Example of Spine

-

Spur: Extension articulating the

junction of the curved and rectilinear stroke.

Figure 4.0.21 Example of Spur

-

Stem: Significant vertical or oblique

stroke.

Figure 5.1.22 Example of Stem

-

Stress: Orientation of the letterform,

indicated by the thin stroke in round forms.

Figure 5.1.23 Example of Stress

-

Swash: Flourish extending the stroke of

the letterform.

Figure 5.1.24 Example of Swash

-

Tail: Curved diagonal stroke at the

finish of certain letterforms.

Figure 5.1.25 Example of Tail

-

Terminal: Self-contained finish of a

stroke without a serif. This term encompasses

various shapes, including flat, flared, acute,

grave, concave, convex, rounded, and more.

Figure 5.1.26 Example of Terminal

5.2 Basic / The font

A full font of a typeface includes more than just

the 26 letters, including numerals and various

punctuation marks. It's crucial to work with a full font

and understand how to use it effectively.

-

Uppercase: Capital letters, including accented

vowels, special characters like ç and ñ, and

ligatures like æ and œ.

Figure 5.2.1 Example of Uppercase

-

Lowercase: Includes the same characters as

uppercase.

Figure 5.2.2 Example of Lowercase

Small Capitals: Uppercase letterforms scaled to the

x-height of the typeface. Found in serif fonts,

they're often part of the expert set. Be cautious of

artificially generated small caps.

Figure 5.2.3 Small Capitals

-

Uppercase Numerals (Lining Figures): Same height

as uppercase letters, suitable for tabular content

or situations requiring uppercase.

Figure 5.2.4 Example of Uppercase Numerals

-

Lowercase Numerals (Old Style Figures/Text

Figures): Set to x-height with ascenders and

descenders, best used alongside upper and

lowercase letterforms. Less common in sans serif

typefaces.

Figure 5.2.5 Example of Lowercase Numerals

Italic: Typically paired with fonts, inspired by

fifteenth-century Italian cursive handwriting. Oblique

variants are based on the roman form of the typeface.

Figure 5.2.6 Example of Italic fonts

Figure 5.2.7 Italic vs Roman

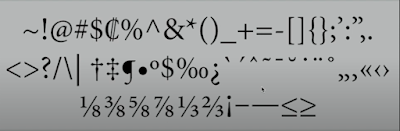

Punctuation and Miscellaneous Characters:

While all fonts include standard punctuation marks,

miscellaneous characters can vary from one typeface to

another. Familiarize yourself with all the characters

available in a typeface before selecting it for a specific

project.

Figure 5.2.8 Punctuation and Miscellaneous Characters

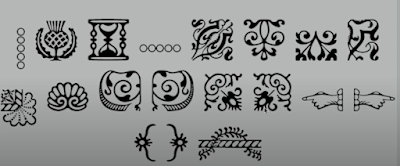

Ornaments:

These are decorative elements often used as flourishes in

invitations or certificates. They are typically provided as

a font within a larger typeface family. Only a few

traditional or classical typefaces include ornamental fonts

as part of the complete typeface family (such as Adobe

Caslon Pro).

Figure 5.2.9 Ornaments

5.3 Basic / Describing

typefaces

-

Roman: Uppercase forms in this style are derived

from inscriptions on Roman monuments. A slightly lighter

stroke in the Roman style is known as 'Book'.

-

Italic: Named for 15th-century Italian

handwriting, on which the forms are based. Oblique

styles are based on the Roman form of the typeface.

-

Boldface: Characterized by a thicker stroke than

the Roman form. Depending on the relative stroke widths,

it can also be termed 'semibold', 'medium', 'black',

'extra bold', or 'super'. In some typefaces (like

Bodoni), the boldest rendition is referred to as

'Poster'.

-

Light: Features a lighter stroke than the Roman

form. Even lighter strokes are called 'thin'.

-

Condense: A condensed version of the Roman form.

Extremely condensed styles are often referred to as

'compressed'.

-

Extended: An extended variation of a Roman font.

Figure 5.3.1 Roman, Italic, Boldface, Light, Condense

and Extended in letterform

5.4 Basic / Comparing typefaces

The 10 typefaces mentioned in the slide cover 500 years of design

evolution. Designers aimed for readability and contemporary style,

and these typefaces excelled, enduring for decades and sometimes

centuries. They reflect how we think, read, write, and print.

Studying them thoroughly is key for beginner typographers, forming

a strong base for early projects and enabling appreciation and

effective use of other typefaces encountered later on.

Figure 5.4.1 Example of 10 typefaces

Typefaces differ in various ways, from their shapes to their emotions.

Understanding these nuances helps shape preferences when choosing

typefaces. Many designers have a few favorites, and some build careers

around just one or two, showing the impact of personal typeface choices.

Figure 5.4.2 Example of "a" and "R"

Lecture 6 |

Letters : Understanding Letterforms

Uppercase letterforms may initially seem symmetrical, but upon closer

inspection, subtle asymmetries become apparent. In examples like Baskerville

and Univers, it's evident how much precision a type designer invests in

crafting letterforms that achieve both internal balance and individual

expressiveness.

Figure 6.1.1 Baskerville 'A'

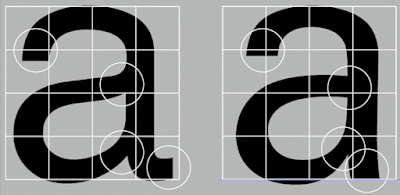

Comparing the lowercase 'a' in Helvetica and Univers, seemingly similar

sans-serif typefaces, unveils distinct nuances. The finishing of stems and the

meeting point of bowls with stems highlight the unique character of each

typeface.

Figure 6.1.3 Helvetica vs Univers

6.2 Letters / Maintaining x- height

The x-height primarily determines the size of lowercase letterforms. It's

important to note that curved strokes, like those in the letter 's', must

extend above the median (or descend below the baseline) to visually match

the height of the vertical and horizontal strokes they connect with.

Figure 6.2.1 Median & Baseline

6.3 Letters / Form / Counterform

Understanding counterforms is crucial. It refers to the space within and

often between the strokes of a letter. It's especially relevant when dealing

with letterforms like lowercase 'r' that lack traditional counters. Mastery

of counters ensures text reads cohesively and legibly.

Figure 6.3.1 Forms and Counter forms of letterforms

Examining letters up close reveals the delicate interplay between form and

counter. It offers insight into a letterform's distinctive attributes and the

art of letter-making. Notably, the 'S' maintains its identity at every scale,

while the 'g' tends to lose definition when isolated from the complete

letterform.

Figure 6.3.2 Helvetica vs Baskerville

6.4 Letters / Contrast

The fundamental principles of Graphic Design seamlessly apply to typography.

Consider the powerful dynamic of contrast, as demonstrated through various

examples. This interplay includes small vs. organic, large vs. machined,

small vs. dark, and large vs. light. These variations showcase the

versatility of contrast in design.

Lecture 7 |

Letters : Typography in Different Medium

In the past, typography was considered complete once a

publication was printed. Skilled typesetters and designers

ensured good typography and readability.

Today, typography isn't confined to paper. It appears on

various screens, influenced by factors like operating systems,

fonts, devices, and screen settings. This means our experience

of typography can vary based on how the page is displayed in a

web browser.

7.1 Print Type VS Screen Type

Typefaces like Caslon, Garamond, and Baskerville are excellent

choices for print. They offer elegance, intellectual appeal,

and readability even at small sizes. These classic typefaces

are versatile and easy to work with, making them ideal for

typesetting in print. The designer's role is to ensure the

text is smooth and flows well, enhancing the reading

experience.

Figure 7.1.1 Type of Print

Typefaces designed for the web undergo optimizations for

improved readability and performance on screens. This

includes adjustments like taller x-heights, wider

letterforms, open counters, heavier strokes, and reduced

contrast. Spacing is also increased, particularly for

smaller sizes. These modifications enhance character

recognition and overall readability in digital environments

such as websites, e-books, e-readers, and mobile devices.

Figure 7.1.2 Type for Screen

A hyperlink is an interactive element, often text or an

image, allowing users to click and navigate to another

document or section. Commonly blue and underlined on web

pages, they change the cursor to a hand pointer when

hovered over.

On-screen, 16-pixel text is similar in size to printed text

in books or magazines for comfortable reading distance.

Printed books often use around 10-point font for close

reading, while on-screen text for arm's length should be at

least 12 points, approximately 16 pixels.

- System Fonts for Screen / Web Safe Fonts

System Fonts or Web Safe Fonts are pre-installed fonts on

various operating systems like Windows, MacOS, and

Android. They ensure consistent display across devices.

Choosing an uncommon, paid font for a website might result

in defaulting to basic fonts like Times New Roman if it's

not available on the visitor's device. Web safe fonts like

Open Sans, Lato, Arial, Helvetica, Times New Roman,

Verdana, and Georgia guarantee compatibility across

different operating systems.

- Pixel Differential Between Devices

The size and proportion of

text on screens vary due to differences in pixel sizes. For

example, 100 pixels on a laptop screen appear differently

than on a larger 60" HDTV. Additionally, there can be

significant variation even within a single type of device.

Figure 7.1.3 Pixel Differential between Devices

7. 2 Static VS Motion

Static typography has limited expressiveness, mainly

using features like bold and italic for emphasis. It's

commonly seen in designs like billboards and posters for

informational, promotional, and formal purposes, relying

on emotional connections with viewers.

Motion typography involves moving text in media like

films and videos. It brings letterforms to life

through animation, creating dynamic visual

experiences. Often used in film title credits and

branding, it synchronizes text movement with

soundtracks, enhancing impact and setting the mood for

the content.

Figure 7.2.1 Static vs Motion

INSTRUCTIONS

EXERCISES

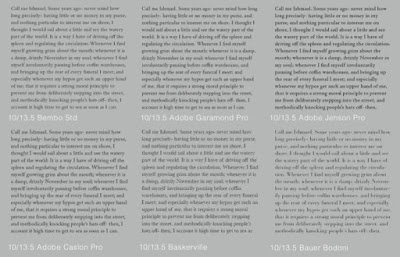

Task 1| Exercises 1 - Type Expression

In this Exercise , we were tasked with creating type expressions using a

set of words: Dizzy, Electric, Fire, Gun, Cry, and Freeze. We were limited

to using only ten typefaces: Adobe Caslon Pro, Bembo, Bodoni, Futura, Gill

Sans, Garamond, New Baskerville, Janson, Serifa, and Univers. The

objective was to convey the meaning of each word through typography and

fonts.

1. Sketches

For this task, I selected “Fire”,

“Slide”, “Gun” and “Electric” in my sketches.We were instructed to

select four out of the seven words ("Dizzy," "Electric," "Fire," "Cry,"

"Gun," "Slide," "Freeze") and sketch their meanings. Graphic elements

were not permitted, and our options were confined to the ten specified

typefaces.

Figure 1.1.1 Sketch of my Type Expression

Before transitioning to Adobe Illustrator CC, I first sketched them out,

aiming to capture the design concepts that came to mind. Typeface

selection wasn't a focal point during the initial sketching of the

words. Rather, the emphasis was on grasping the essence of the intended

design. Subsequently, I proceeded to digitize the type expressions and

made minor adjustments to the designs.

2. Digitisation

For the word "Slide," I conveyed a sense

of fluidity through the arrangement and form of the font, creating the

impression that the text itself was gliding forward. This design evoked

a feeling of speed and motion.

Figure 1.1.2 Digitising the word "slide"

In the case of "Gun," I opted for a font that exuded solidity and

strength, utilizing strokes and lines to convey the weightiness and

power associated with weaponry. This design ensured that viewers could

instantly grasp the intended meaning of the word.

Figure 1.1.3 Digitising the word "gun"

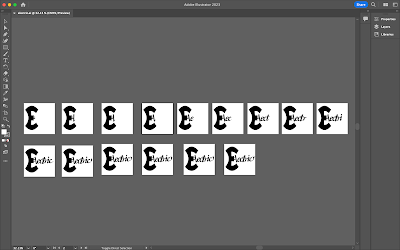

With "Electric," I utilized a cursive font to convey the sense of

electric flow. Through adjustments in letter spacing and arrangement,

this created a visual effect that evoked the visual flow of electrical

current.

Figure 1.1.4 Digitising the word "electric"

Finally, for "Fire," I selected a font that appeared as if it had been

charred to ashes. Through the form and arrangement of letters, I

created a visual effect resembling the letters being consumed by the

fire.

Figure 1.1.5 Digitising the word "fire"

Final Outcome

Figure 1.1.6 Final Type Expression - jpg | Week 3 (9/10/23)

Figure 1.1.7 Final Type Expression -pdf | Week 3 (9/10/23)

3. Animation

After digitizing four different words,

I ultimately chose "Electric" as my final animated word.

Figure 1.1.8 progress of animation using Adobe Illustrator

In the video, Mr. Vinod proficiently demonstrated how to use Adobe

Illustrator and Photoshop to create a basic type animation. Throughout

the production process, I identified some areas for improvement,

particularly in achieving the desired electric-like effect. To address

this, I recognized the necessity of adding more frames and adjusting

the letter positions to enhance the overall visual impact.

Figure 1.1.9 progress of animation using Photoshop

And lastly, here is the ultimate result of my animation for the word

"Electric".

Final Animation

Figure 1.1.10 Final Animation

Task 1| Exercises 2 - Text Formatting

1. Minor exercises on kerning and tracking

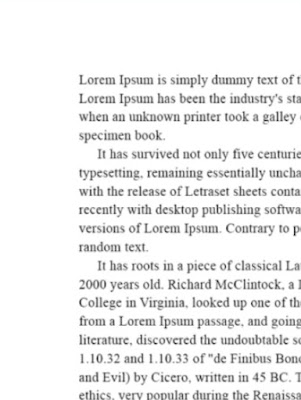

For Exercise 2, we will be crafting a conclusive layout that encompasses

an array of text formatting elements, including kerning, leading,

paragraph spacing, alignment, and more. This task aims to hone our

proficiency in spatial organization and refining information hierarchy.

Adobe InDesign will be our tool of choice for this exercise, enabling us

to skillfully manipulate these aspects for a polished final layout.

Figure 1.2.1 with kerning

Figure 1.2.2 without kerning

2. Exercises on Text Formatting

Figure 1.2.3 Progress of text

FINAL OUTCOME

HEAD

Font/s: Univers LT Std

Type Size/s: 30pt , 18pt

Leading: 18pt

Paragraph spacing: -

BODY

Font/s: Univers LT Std

Type Size/s: 9.5pt

Leading: 12

Paragraph spacing: 4.233mm

Characters per-line: 60

Alignment: Justify with last line aligned left

Margins: 38mm top, 12.7mm left + 12.7mm right + 34.5mm

bottom

Columns: 4

Gutter: 5mm

Figure 1.2.4 Text formatting layout - jpg | Week 5

(23/10/23)

Figure 1.2.5 Final Text formatting layout - pdf | Week 5 (23/10/23)

Figure 1.2.6 Text formatting layout (grids) - jpg | Week 5 (23/10/23)

Figure 1.2.7 Final Text formatting layout (grids) - pdf | Week 5 (23/10/23)

FEEDBACKS

Week 3 (9/10/23) :

General Feedback - I sketched four distinct words: "Fire,"

"Slide," "Gun," and "Electric." This exercise provided an opportunity

to delve into the realm of font design and explore how to visually

represent these words.

Specific Feedback - Regarding "Electric," I realized I

needed to minimize the use of graphical elements and opt for a more

suitable typeface. While preserving the original concept, I executed it

differently. As for "Fire," I learned that any form of distortion,

including curving edges, was not permissible. After refining my design,

I found it to be an improvement from the initial version.

Week 3 (9/10/23) :

General Feedback - During this week, Mr. Vinod provided a

comprehensive review of the completed exercises by all students,

offering invaluable feedback. After reviewing our sketches for Task 1,

he directed us to an instructional video on digitizing artwork using

Adobe Illustrator.

Specific Feedback - Mr. Vinod offered invaluable

guidance in correcting errors within my class exercise. Specifically for

"Electric," he recommended reducing negative space and refining its

composition to create a more impactful visual.

Week 4 (16/10/23) :

General Feedback - Expressions match the meaning of the

words well, showcasing strong compositional skills. It's important to

exercise restraint with distortion and consider how each chosen font

complements the meaning of the respective word. The font selection

should harmonize with the essence of the word being worked on.

Specific Feedback - Mr. Vinod advised me to focus on

adjusting the spacing for a better result. Regarding the animation of

"Electric," he pointed out that it is currently too fast. He suggested

allowing the type to descend more slowly, enabling viewers to observe

the words on the ground elongating. This adjustment will enhance the

overall visual impact.

Week 5 (23/10/23) :

General Feedback - Use InDesign to complete Task 1 Exercise

2 - Text Formatting. Good layouts, ragging, and cross alignments. Font

size corresponds to the leading. No hyphenations, widows, or orphans

present.

Specific Feedback - Make sure all layouts are neat, don't

make the text too messy. Avoid using two different fonts, and adjust the

spacing of the fonts appropriately—neither too far apart nor too close

together.

REFLECTIONS

Experience:

Over the course of this class, I've delved into the intricacies of

typography. The initial stages involved sketching, which presented a

challenge due to the limited use of typefaces and the absence of

graphical elements. Coming up with unique ideas amidst these

constraints was a stimulating exercise. As we transitioned to the

digitalization phase, I encountered a learning curve with Adobe

Illustrator, having been more accustomed to Photoshop. Navigating

through formatting and arrangement nuances during the practical

sessions was a worthwhile endeavor. Additionally, the text formatting

exercise proved unexpectedly demanding, particularly in grasping the

baseline grid intricacies.

Observations:

Throughout this journey, I've come to appreciate the symbiotic

relationship between typography and various design elements.

Alignment, for instance, emerges as a pivotal factor in establishing

hierarchy and visual weight. It's fascinating to witness how letters

can morph into shapes or images, adding depth to the visual narrative.

Elements like movement, scale, contrast, and value also play crucial

roles in shaping the overall typographic composition.

Findings:

This exploration into typography has illuminated the depth of its

rules and terminology, requiring a diligent approach to absorb and

apply them effectively. The process has underscored the importance of

meticulous scrutiny of every detail, coupled with a rigorous

self-critique, as the path to refinement. Simple typefaces, often

taken for granted, reveal a rich design heritage, each carrying a

profound and layered history. Designing and arranging type entails a

multifaceted consideration of factors that contribute to the overall

visual impact. Through this journey, I've unearthed a newfound

appreciation for the art and science of typography, realizing that

even within constraints, creativity finds its most compelling

expressions.

FURTHER READING

- "A Type Primer" by John Kane

Figure "A Type Primer" by John Kane

After reviewing the books Mr. Vinod provided, I have chosen "A Type

Primer" by John Kane as my selection. This book likely offers a

comprehensive understanding of typography, encompassing font history,

classification, and anatomy. It also imparts fundamental principles

for selecting typefaces, which play a pivotal role in layout and

design, conveying unique emotions and atmospheres.

The insights provided in the book offer practical advice on selecting,

combining, and applying typefaces in real-world design scenarios,

along with considerations for typesetting. This knowledge instills

confidence in font selections and ensures they align with the demands

of the design project.

-

"The Vignelli Canon" by Massimo Vignelli

Figure "The Vignelli Canon" by Massimo Vignelli

"The Vignelli Canon" is a design manual by Italian designer Massimo

Vignelli, offering valuable insights into design principles and

methodologies, including typography, color, and layout. It emphasizes

standards and clarity in design, making it a valuable resource for

designers at all levels.

- "Just My Type" by Simon Garfield

Figure "Just My Type" by Simon Garfield

"Just My Type" is a book about fonts and typography written by British

author Simon Garfield. It provides a humorous exploration of various

types of fonts, delving into their history, design principles, and

applications. The book presents the significance of fonts in our daily

lives in an engaging and light-hearted manner, making it a delightful

read for those interested in fonts and typography.

- "Typographic Systems" by Kimberly Elam

Figure "Typographic Systems" by Kimberly Elam

"Typographic Systems" is a book by Kimberly Elam that explores the

fundamental elements of typography and their impact on design.

Through practical examples and illustrations, it teaches how to

create effective typographic systems for visually appealing and

functional designs. This book is a valuable resource for designers

and students looking to master typography principles.

Figure "Typography Referenced"

"Typography Referenced" is a comprehensive reference book on font

design and layout. It covers the history, technical details, and

practical aspects of typography. The book also provides valuable

examples and advice for designers looking to effectively use fonts

in their work. It's a valuable resource for anyone interested in

the art of typography.

top^

QUICK LINK

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment